Med-Fit Tech Assistant

Human Anatomy - Learning Module #2

The Skeletal-Articular System

Part B

Part B: The Articular System - Synovial Joints

Learning Objectives:

Basic Structure and Function of a Synovial Joint

Synovial joints are characterized by the presence of a joint cavity. The walls of this space are formed by the articular capsule. Fibrous connective tissue is attached to each bone just outside their articulating surfaces. The bones articulate with each other within the joint cavity.

Learning Objectives:

- Identify the basic structures of a synovial joint.

- Describe the 6 types of major synovial joints by articulation.

- Name, locate, and classify the major synovial joints of the human body.

Basic Structure and Function of a Synovial Joint

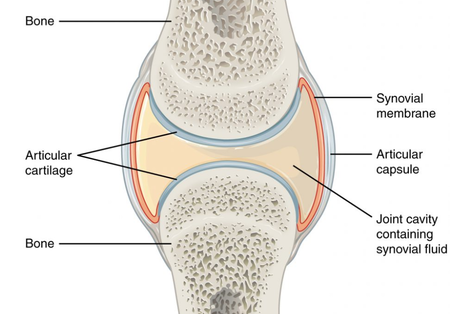

Synovial joints are characterized by the presence of a joint cavity. The walls of this space are formed by the articular capsule. Fibrous connective tissue is attached to each bone just outside their articulating surfaces. The bones articulate with each other within the joint cavity.

Friction between the bones is prevented by the presence of the articular cartilage, a thin layer of hyaline cartilage that covers the entire articulating surface of each bone. The articular cartilage acts like a Teflon® coating over the bone surface, allowing the bones to move smoothly against each other without damaging the underlying bone tissue.

Lining the inner surface of the articular capsule is a thin synovial membrane. The cells of this membrane secrete synovial fluid, a thick, slimy fluid that provides lubrication to further reduce friction between the bones of the joint. Synovial fluid also provides nourishment to the articular cartilage, which does not contain blood vessels.

Outside of their articulating surfaces, the bones are connected together by ligaments, which are strong bands of fibrous connective tissue. These strengthen and support the joint by anchoring the bones together and preventing their separation. Ligaments allow for normal movements at a joint, but limit the range of these motions, thus preventing excessive or abnormal joint movements.

Additional support is provided by the muscles and their tendons that act across the joint. A tendon is dense connective tissue that attaches a muscle to bone. As forces acting on a joint increase, the body will automatically contract the muscles crossing that joint, thus allowing the muscle and its tendon to serve as a “dynamic ligament” to resist the forces and support the joint. This type of indirect support by muscles is very important at the shoulder joint, for example, where the ligaments are relatively weak in order to allow greater range of motion.

The 6 types of Synovial Joints

The six types of synovial joints allow the body to move in a variety of ways.

Lining the inner surface of the articular capsule is a thin synovial membrane. The cells of this membrane secrete synovial fluid, a thick, slimy fluid that provides lubrication to further reduce friction between the bones of the joint. Synovial fluid also provides nourishment to the articular cartilage, which does not contain blood vessels.

Outside of their articulating surfaces, the bones are connected together by ligaments, which are strong bands of fibrous connective tissue. These strengthen and support the joint by anchoring the bones together and preventing their separation. Ligaments allow for normal movements at a joint, but limit the range of these motions, thus preventing excessive or abnormal joint movements.

Additional support is provided by the muscles and their tendons that act across the joint. A tendon is dense connective tissue that attaches a muscle to bone. As forces acting on a joint increase, the body will automatically contract the muscles crossing that joint, thus allowing the muscle and its tendon to serve as a “dynamic ligament” to resist the forces and support the joint. This type of indirect support by muscles is very important at the shoulder joint, for example, where the ligaments are relatively weak in order to allow greater range of motion.

The 6 types of Synovial Joints

The six types of synovial joints allow the body to move in a variety of ways.

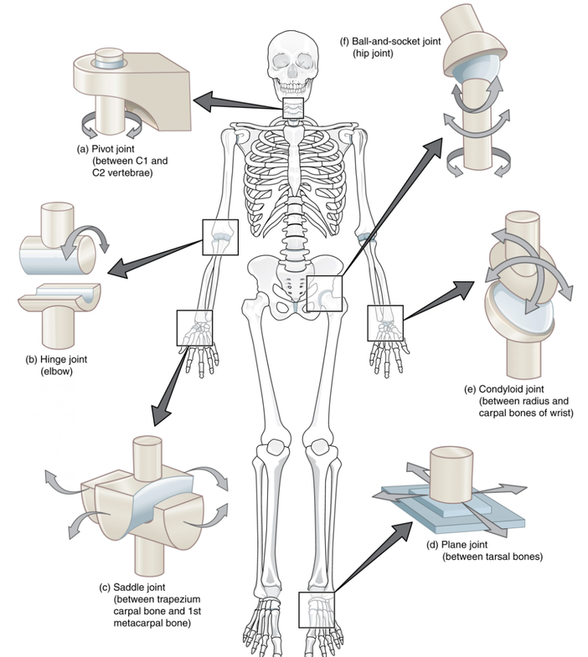

- Pivot Joints allow for rotation around an axis, such as between the first and second cervical vertebrae, which allows for left-right rotation of the head.

- Hinge Joints of the elbow and knee work like a door hinge allowing mobility on a single axis and providing adequate support for heavy loads.

- Ball & Socket Joints of the shoulder and hip allow for multi-axial movements while still providing adequate support for heavy loads.

- Saddle, Plane, and Condyloid Joints are complex structures in the hands and feet that allow a variety of movements while providing adequate support and range of motion.

Functional Classification of the Major Synovial Joints

Pivot Joints – only allow for rotation.

Hinge Joints – only allow flexion and extension along a single axis.

Ball-and-Socket Joints – multi-axial joints allowing for the greatest range of motion while providing the appropriate amount of support in each direction of movement, including: flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, rotation, and circumduction.

Condyloid Joints – allow for flexion, extension, and limited abduction, adduction, and circumduction.

Saddle Joints – allow for flexion, extension, and greater abduction, adduction, and circumduction than the condyloid joints of the wrist, hand, and foot.

Plane Joints – allow for limited gliding movements between bones in a variety of directions. Movements are usually small and tightly constrained by surrounding ligaments.

Pivot Joints – only allow for rotation.

- Neck – between C1 and C2 (atlanto-axial) joint.

- Forearm – between the ulnar and radius (distal to the elbow).

Hinge Joints – only allow flexion and extension along a single axis.

- Elbow – between the humerus and the ulna.

- Knee – between the femur and the tibia.

- Ankle – between the tibia/fibula and the talus (the superior tarsal bone).

- Finger & Toe Knuckles – between the proximal, middle, and distal phalanges.

Ball-and-Socket Joints – multi-axial joints allowing for the greatest range of motion while providing the appropriate amount of support in each direction of movement, including: flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, rotation, and circumduction.

- Shoulder – between the shallow socket formed by the clavicle and scapula and the ball of the humerus.

- Hip – between the deep socket of the ileum (pelvis) and the ball of the femur.

Condyloid Joints – allow for flexion, extension, and limited abduction, adduction, and circumduction.

- Wrist (radio-carpal joint) – between the distal end of the radius and the scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum carpal bones.

- Hand Knuckles (metacarpal-phalangeal joints) – between the distal end of the metacarpal bones and the proximal phalanges.

- Foot Knuckles (metatarsal-phalangeal joints) – between the distal end of the metatarsal bones and the proximal phalanges.

Saddle Joints – allow for flexion, extension, and greater abduction, adduction, and circumduction than the condyloid joints of the wrist, hand, and foot.

- Thumb (first carpo-metacarpal joint, base of the thumb) – between the trapezium (a carpal bone) and the first metacarpal bone.

- The sterno-clavicular joint (between the sternum and proximal clavicle) is also classified as a saddle joint, but with much less mobility than the thumb and more ligaments to support the shoulder movements.

Plane Joints – allow for limited gliding movements between bones in a variety of directions. Movements are usually small and tightly constrained by surrounding ligaments.

- Neck & Trunk – between vertebrae C1--L5 (inter-vertebral joints). The superior and inferior articular processes of adjacent vertebrae (zygapo-physial joints).

- Wrist - between the carpal bones (inter-carpal joints).

- Foot – between the tarsal bones (inter-tarsal joints).

- Shoulder Girdle – between the distal clavicle and acromion process of the scapula (acromio-clavicular joint).

Module #2B: LAB

In front of a full-length mirror, point to your body structure listed below, name its major synovial joint(s), classify the joint(s), and list its directional movements by memory.

- Neck, Trunk, Shoulder, Elbow, Forearm, Wrist, Hip, Knee, Ankle